From “Murali Vani”, Sri B V K Sastry Felicitation Volume

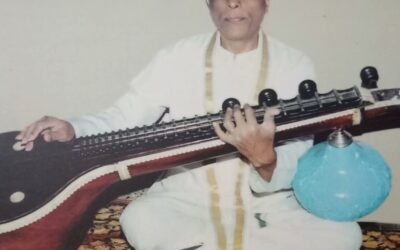

Among the titles held by Maharajapuram Viswanatha Iyer, a notable one was that of ‘Sangitha Bhoopati’, conferred on him decades ago by an elite gathering of music lovers in the Tanjore district. Possibly, the place of his birth – Maharajapuram, may itself have suggested the form of this honour. Or was it the imposing figure he was on the platform that gave rise to the idea? However that may be, the title had given rise to many a witticism, a number of them authored by the musician himself.

One of these comes to the writer’s mind: During a recital given by Viswanatha Iyer, a certain member of the audience clamoured for the raga Darbar. Whereupon Maharajapuram remarked to the rasika that it would be superfluous for him to sing the raga, since he was already in a darbar, meaning thereby that, with a ‘Sangitha Bhoopati’(King of the Music World) presiding, the sabha had become a darbar!

Actually, Maharajapuram did not himself attach any pretentious significance to the title. Indeed, anyone who came even into casual contact with him could not decide which aspect of Maharajapuram’s personality he enjoyed more – his lively sense of humour, or his energetic music. Though jovial by temperament, this virtuoso’s approach to music was in no way flippant. Uncertain at first on the platform, as he warmed up sufficiently to still his gay spirit, he really got into the mood: the modal panorama that he unfolded now was as exquisite in its diversity as it was enthralling in its aesthetic nuances.

Yes, ‘mood’ – or manodharma, as it is called – was the dominant force in Maharajapuram’s music. Each recital of his seemed to possess an air of unpredictability. Naturally, his music carried far on the wings of his manodharma, had always a touch of originality. Often the same raga sung by him in one recital would be entirely different in the next, without of course overriding its basic element and sentiment. When he was carried away by his flights of fancy into realms unknown, his music was overawing.

I remember one such occasion when Maharajapuram began, as usual, by retailing jokes, but suddenly assumed a serious air, on the concert platform. His voice, as unpredictable as his mood, was also not amenable at first. Naturally, the initial pieces sounded rather perfunctory. When he took up the raga Suddha Dhanyasi – a pentatonic mode which is generally dismissed with the singing of a composition in it before any serious attempt at elaboration – it was expected that he would follow the customary line. But, in the alapana prelude he startled the audience by suddenly unfolding a curve in an astonishing tonal form. The movements following came in such rapid succession and in such original and daring patterns as to make the audience wonder whether Maharajapuram was at all moving on the right track. Nevertheless, the subsequent part of the kacheri consisted of modes daringly rendered and exuding a richness of rasabhava: the climax of it all was his favourite raga, Mohanam, another pentatonic mode which is universal and perhaps as old as man himself.

Speaking of Mohanam reminds me of the classic comment of the late “Kalki” Krishnamurthy on the title ‘Sangita Bhoopati’. “The title is very apt.” said “Kalki”, “considering that, in the Hindustani, Bhoop corresponds to the Mohanam of the South. Maharajapuram’s indisputable hold on Mohanam made him also an ideal Bhoopati or master of Bhoop!”

Anyway, Maharajapuram did not seem to be unduly affected by such encomiums, or by honours showered by his admirers. He seemed to take them in his stride with the grace and humility of the true artiste. He was something of an epicure, prizing the good things in life. He was fond of perfumes and was always well dressed, often in silks, though not exaggeratedly fastidious. His very appearance was suggestive of buoyancy. The rotund figure topped by a bull-neck and a broad face lit up by a smile, the ears adorned with glittering diamond studs, and the few straggling grey hairs tied behind in a pea-sized knot had a touch of comicality about them. And his penchant for sparking off into witticisms and puns at the slightest provocation made his company as entertaining as his music was elating.

His music, too, had a singularly resilient quality, the modal patterns emerging in delightful effervescent forms, often reminding one of the notes of the nagaswaram. Their unexpected facets and expansive dimensions suggested that probably, the nagaswaram played a dominant role in shaping his art.

Viswanatha Iyer was born on 15-9-1896 at Maharajapuram, where the atmosphere was always laden with the haunting music of the nagaswaram. Situated on the banks of the Kaveri, the village of Maharajapuram, in Tanjore district is close to Tirukkodikaval, with a famous shrine of Siva, and familiar in the recent past as the place where the master violinist, Krishna Iyer, lived. There are festivities, throughout the year in temple there – as in any of the important shrines of Cholamandala – when some of the best known nagaswaram players come and offer choice flowers of their art. Young Viswanathan would play truant and tread the path to the temple to participate in the festivities. Particularly the nagaswaram music of the great Thirumarugal Natesan (uncle of the late Rajaratnam Pillai) seemed to haunt him. “While listening to that divine music, I would forget my school, my books and my home.” would say Maharajapuram.

Naturally he was questioned on the point by his father after he had for many days repeatedly stayed away late, sometimes even overnight. “Of course, I did not hide anything from him and told him of my infatuation with music, particularly with nagaswaram music of Thirumarugal Natesan, which seemed to obliterate the memories of everything else for me. Such a retort, which would normally have merited a thrashing had the contrary effect on my father. After all, he too was very fond of music, and Thirumarugal Natesan was one of his friends…..”

Anyway, that brought to an end Viswanathan’s schooldays, and his father, Ramayyar, a mirasdar, thought it would be more fruitful to allow his son to pursue his zeal for music, eventually deciding to place him under another of his friends, Umayalpuram Swaminatha Iyer, a great scholar-exponent of music and a disciple of Maha Vaidyanatha Iyer.

When he came to his guru, Viswanathan could already sing many ragas with facility. So, after a brief test, Umayalpuram decided to put him immediately on advanced course of study. “Perhaps I was one of the very few who started straight away with a varnam, skipping all the preliminaries” Maharajapuram said to me, with a twinkle in his eyes. The apprenticeship with Umayalpuram was very steady and uneventful and the musical lessons imparted by the guru were methodical. With his alert mind, the pupil grasped the science of music quickly, even if his conviviality often interfered with the seriousness of the pursuit. An episode in his career, which possibly proved a turning point, will illustrate this aspect.

Among Umayalpuram’s pupils was a lady who was fairly advanced in her studies. One day, in the midst of a lesson, when development of the swaraprastara (sargam) in an unusual raga was being executed. Umayalpuram asked Maharajapuram to join in the singing Unfortunately, the young man could not sing swara to that particular range. Umayalpuram smiled and remarked: “How is it you are unable to perform a feat managed with such facility by a lady?”

The matter was didmissed as a joke by the guru, but the pupil took it to heart. “I could not sleep that night,”said Maharajapuram, “particularly at the thought that I had been put to shame by a lady. “He wanted to master the intricate technique of swaraprastara, and obsessed with the idea, he repaired every day to one of the pavilions (mandapams) by the Mahamakam tank in Kumbakonam and there practised strenuous music exercises to the point of hurting his vocal chords.

On one such occasion, one Vengu Iyer, a musician, whose proficiency in the art unfortunately remained unrewarded, came to Viswanathan and enquired after him. Learning the reason for the strenuous practice, Vengu Iyer initiated him into certain exercises he had assiduously developed, which in their turn opened the eyes of the young man to the secrets of the art and widened the horizons of his musics. A few days later, when the lady mentioned above was having a practice session, Maharajapuram offered to sing the swara, Umayalpuram’s first reaction was one of plain amusement. However, he asked the pupil repeatedly to sing the swara for different modes – some of them difficult – in all of which young Viswanathan came out with flying colours, much to the astonishment and delight of his guru.

Maharajapuram had now arrived at a stage of maturity calling for a re-examination of his art. He wanted to correct the faults in his music and improve the tala-laya aspect. A strange circumstance helped him to gratify his urge. His brother had invited one of his musician friends to his home, to hear young Viswanathan (of whose music the family was proud). This friend was Palani Rangappa Ayyar, and eminent percussionist, who played exquisitely on the mridangam, the ghatam and the harmonium. The result of this contact was that young Viswanathan followed Rangappa Ayyar to Palani to have solid grounding in laya.

… to be continued