Kala Samvada – Smt. Padma Chittampalli : Documenting Legacy

–Janani Murali

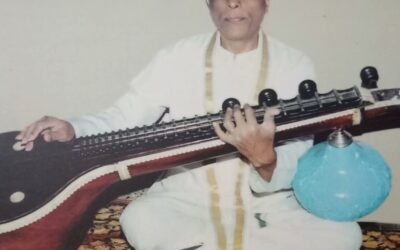

Padma Chittampalli hails from a musical family in Mysore. Her father was a disciple of Mysore Vasudevachar and Tiger Varadachar. Her mother was a Tamil scholar. Padma and her sister trained in music under Vid. Swaramurthy Rao and Vid. Padmanabha Rao. With a double Masters degree in Medial information and public health from Columbia university, while pursuing her PhD at Columbia University, she met her Guru Nala Najan. From him she imbibed three different traditions of the Deccan- Tanjore, Bhagavata mela and Mysore sampradaya. She documents his legacy and her learning years with him in her series of books published recently. Ananya Kalasinchana speaks to her of the journey thus far and the birth of these grand books on dance, dancer and legacy.

Padma Chittampalli hails from a musical family in Mysore. Her father was a disciple of Mysore Vasudevachar and Tiger Varadachar. Her mother was a Tamil scholar. Padma and her sister trained in music under Vid. Swaramurthy Rao and Vid. Padmanabha Rao. With a double Masters degree in Medial information and public health from Columbia university, while pursuing her PhD at Columbia University, she met her Guru Nala Najan. From him she imbibed three different traditions of the Deccan- Tanjore, Bhagavata mela and Mysore sampradaya. She documents his legacy and her learning years with him in her series of books published recently. Ananya Kalasinchana speaks to her of the journey thus far and the birth of these grand books on dance, dancer and legacy.

The beginnings

I had a problem breathing in New York. The doctor suggested a few basic exercises but insisted that I must begin working out if I were to stay healthy in this weather. He suggested I go join a gym but I didn’t fancy it. My older sister who I lived with at that time suggested that I try Bharatanatyam class. The idea didn’t sound bad so I figured ‘why not’. Govinda, a performer she had recently seen – was introduced to me but he felt that he was not qualified enough to teach. He instead suggested that I meet his teacher who was to return shortly from Italy.

Learning dance in New York was difficult in terms of space- In India, a part of the home was converted into dance class space. But in New York, studios had to be rented by the hour. Another friend Anita who had been learning Bharatanatyam also encouraged me to come and try a class. So, I agreed to go with her to ‘Ansonia’, a large building with a studio in it where their classes were run. I was greeted by a wall full of mirrors – and I was taken aback- I had seen nothing like this and had not imagined that a dance class looked like this. 10 other students stood there- all of them American. I was probably the only Indian there waiting and in walked in a young man in blue jeans and a sweatshirt, a large cigarette holder in hand. He took his Thalam and started class. That first class was not what I imagined a dance class to be. I had arrived there in a grand silk saree and here he was, looking like any average American on the street, conducting a Bharatanatyam class. After an hour and a half, I came out of class, legs shaking. I thought I’d have to just sit for a few hours before I could walk down. As I walked back home, I thought it wasn’t for me. My sister on the other hand was quite exited about my dance class and insisted that I should return. In my mind, the debate to return or leave was strong. I returned the next class, but only so I could inform him in person that I was not going to continue. I thought it was inappropriate to say this on the phone. So, for the second class, I went back. And while class was going on, it dawned on me that there was more to dance than just executing movement. My curiosity was a bit piqued now but the debate was still rife in my head.

Differences beyond recognition:

Most students called him by his first name. After class, he would encourage everyone to sit down next to him to discuss and chat. These habits were almost blasphemous to me. I came from a space where I found it even incorrect to sit while the teacher spoke. I had also just walked into class and had not followed any of the traditional rituals of starting an education in dance. This made me uncomfortable too. I was at that time pursuing a PhD at Columbia University – so to pursue dance amidst academics was also adding to my dilemma. After that second class, Nala noticed that I was in some dilemma, sat me down and spoke. I had a chat with him and he eased me into the fact that this was a beautiful learning environment. I decided to continue.

Teacher to Guru:

When does a teacher become a Guru? I recognised that this was a serious Guru at that second class. His profound knowledge became apparent in him talking. It was difficult to not recognise his vidwath. The ease with which he moved through languages, treatises and technique -comes only from being that knowledgeable. I talk of his own journey of going from a teenager to a Guru in my book. Nala learnt from the masters of the time. What he imbibed was not just technique or theoretical knowledge but a complete understanding of the cultural context that gave rise to the dances. Be it the Bbhagavathmela in Melattur, Kuchipudi, javalis and padam that he learnt from devadasis, kathak from Sunderlal Gangani, Chauu from Seraikela, Bharatanatyam from Mugur Sundaramma and Nanjangud Nagarathnama or Muthukumara Pillai of Tanjore. Nala was merely a teenager when he began to understand the true depth of what dance meant. He stayed with his gurus, experienced life in the heartlands and came to know that dance and life were not separate entities. This showed in his approach to dance later as a teacher and as my guru.

The journey progresses: a non-Indian eco system

My sister kept reminding me that I lucked out to find such a guru halfway across the world. Nala choreographed for me- with a holistic perspective. For example, when he taught a song, he would ensure that the class had a good smattering of that particular language to be able to create the right ethos of the language, the people and the cultural context of the land.By the time I had learnt a Varnam, I was crazy about dance. I moved into an apartment with bare minimum furniture so that I could have classes with him one-on-one. And he began to relax with his lessons too- for there was no restriction of the pay-by-the-hour studio. So then, classes became longer- allowing for both of us to engage deeper with dance. My apartment became a second studio for many others who wanted the luxury of time and to learn dance without the hassles of restricted time.He was a guru that taught generously with no egoistic notions of his students becoming better than him. My parents by now were aware that I was pursuing dance seriously. While my father and grandmother were happy, my mother was apprehensive because at that time, orthodox families still considered dance to not belong. Nevertheless, she came around to supporting my pursuit of dance.

Documenting begins…

When we agreed to have one-on-one lessons, Nala wanted that I write down everything that transpired in the class, whether I found it relevant then or not. Discussions that happened before and after lessons too were to be recorded. I found that it could a tall ask and told him so, but he brushed it off saying I’d be perfectly ok.Nala had a small collection of music recordings from his masters. One day he came across my notebook with my music lessons. He asked that I sing and then realised that he wanted to take from my music repertoire and create a larger repertoire in dance.

Were there compositions that yielded to dance more than others? No. He was taught by his teachers and he believed so and I believe that any composition yields itself to dance. From the moment that these songs began to add to our dance repertoire, the documentation started to become a project in itself of notating the music and dance that arose from then on. He was very Indian at times and very American at times, both perspectives that came through with ease in his personality and in his teaching.

I began to document the songs he taught, notations that had been lost but recordings that we had, sometimes recording mistakes that were commonly made in lyric and the correct version of it. There are words and phrases that are culturally specific and translating them into English would take away from their meaning – we would document these specificities, elaborating the context and arriving at an acceptable version. We also discussed songs that were not choreographed and discussions that led to these decisions were elaborated as well.

And continues…

And continues…

Nala became family, relying on my father for his expertise on the epics and certain other texts. He was true to the art to the extent of going against the grain where he felt it was necessary to clarify mistakes made by others. I see even today that most dancers use very few Hastas in their Abhinaya. But Nala came from enriched traditions and having imbibed the Bhagavatamela too, his hasta viniyoga was exceptional. Drawing from the varied traditions that he imbibed gave him a tremendous corpus to draw from and also pass on. He was so true to his art that he even questioned his Gurus in the Mysore Sampradaya about the ‘dances that he had not learnt’. His teachers found it amusing but his intent was to come back to learn more – which unfortunately never happened due to several limitations.

Reflections…

I see today that the Mei Adavu has become a rarity. A teacher upon being asked brushed it off as unimportant. I also came across an instance of a popular Varnam being interpreted wrongly because the lyric had not been given its due importance. As teachers, the importance of research and diligent understanding is undeniable. With my books, the purpose is to document the legacy that laid immense importance on these very aspects and every subtlety of dance and its ethos. Documenting here my experience of learning from him and his choreography of the music repertoire that I had learnt from my music teachers has been exhaustive. I assume that there are many teachers, including teachers of Nala – whose work remains undocumented. If documented, that would have been even more valuable than the treatises or texts that we today read or refer to as authoritative. The need to document such artistes and their legacy is enormous. A meagre portion of the work of the grandmasters is documented in the libraries of Tanjore, I understand. How much we would gain if all their work was documented.

When Nala asked his Mysore teachers for the compositions that they taught him, they at first wondered what he would do with songs written in Kannada- a language he couldn’t understand. More importantly, writing a song and their comments on its choreography was an exercise they had never done before. But upon his insistence, they did write and we now stand to gain from their manuscripts. On the other hand, today, the quality of writing in terms of research is not all of high standard. To have mediocre work stand on par with work of high quality is unfortunate.

I received from my Guru what he perceived as valuable. I hope that the value of his legacy is passed on to the generations to come.

**********