Chapter 2

THE CONCEPT OF MODAL SHIFT OF TONIC

2.1 Introduction

In the previous chapter the concepts of adhara shadja, the seven notes, and the 12 swarasthanas were discussed. Here we shall deal with an important concept in Indian music known as the modal shift of tonic.

In music concerts, vocalists sometimes apply the technique of modal shift of tonic to demonstrate their scholarship and mastery over the swaras. In this process, without changing the sruti of the tambura (the drone) and by changing only the reference note, different ragas are produced. This process is commonly known as the modal shift of tonic. However, if the musician is not careful enough such a shift of tonic of adhara shadja does more harm than good as the changed adhara shadja confuses the listener. It is therefore essential that this technique be used judiciously and sparingly.

In reality, the usage of the modal shift of tonic in vocal music is only a very small application area of this technique. This is actually a very powerful technique from a theoretical point of view. Using this technique one can get information about:

1. The relative frequencies of the 12 swaras;

2. The fundamental properties of the 12 swaras, their building blocks

1. and the entire gamut of the 22 srutis.

2. The relationship between the swaras and the concept of consonance

3. in terms of vadi-anuvadi-samvadi and vivadi swaras; and

4. The generation of new ragas from a given raga.

Apart from the above, the modal shift of tonic is also useful in instrumental music. It can be used effectively in vadya vrindas or instrumental orchestra. In instrumental classical music orchestra, it is possible to adapt this technique in a very effective way, leading to new musical experiences. When a raga is being expounded in an instrumental

orchestra, a suitable blend of the raga with those resulting from the modal shift of tonic can result in new and pleasing musical experience. There are some basic differences in the approaches to vocal music and instrumental music. The technique of the modal shift of tonic is more appropriate to instrumental orchestral music than vocal music. Although orchestral music employing the modal shift of tonic is being successfully attempted, there is still much scope for improvisation.

2.2 The concept of modal shift of tonic

Playing or singing a raga by making another swara in its scale as the reference note or adhara shadja is known as the modal shift of tonic. Depending on the staring raga and the note chosen for reference, a new raga may emerge. For this new raga, the reference note chosen earlier becomes the adhara shadja. Often shifting of the tonic or adhara shadja results in a group of notes that may not make a meaningful combination. In such cases, the modal shift of tonic becomes a futile exercise. On the other hand, if the group of notes produced by the modal shift results in a new raga, the tonic shift is said to be successful.

The modal shift of tonic is one of the effective methods of creating new ragas. In the past, several ragas have been created using this approach.

The modal shift of tonic, in musical literature, is called srutibheda or grahabheda. It is also called as moorchana. The reference note chosen for the process is known as the moorchana swara.

If a raga gives birth to at least one meaningful raga by srutibheda, such a raga is called a moorchanakaraka raga. If no new raga results from any of the possible moorchana swaras, then such a raga is called an amoorchanakaraka raga.

We may now illustrate the modal shift of tonic or srutibheda using an example. Consider raga Mohana whose arohana is as follows:

S R2 G3 P D2 Ṡ

In this raga, if we now choose rishabha (R2) as the adhara shadja and sing the swaras R G P D S R, there result the swaras S R M P N S – the arohana of the raga Madhyamavati. In the same way the avarohana of the

original swaras of raga Mohana sung as R S D P G R will result in the notes S N P M R S – the avarohana swaras of Madhyamavathi. Thus the reference note R2 of raga Mohana leads to the raga Madhyamavati. While the original scale of Mohana remains unaltered in the original pitch, it appears as raga Madhyamavati in the changed pitch which uses R2 as the reference note.

In a similar way, there result the ragas – Hindola from gandhara (G3), Suddha Saveri from panchama and Suddha Dhanyasi from dhaivata (D2).

In the above example, every note of Mohana results in a new raga. However, it is not necessary that every raga have this pro;perty. In some cases no new raga results from any of their notes, and as already mentioned, such ragas are known as amoorchanakaraka ragas. In other cases, only some of the notes in a raga may give rise to new ragas. If all the swaras in a raga lead to new ragas by modal shift of tonic, such a raga is called a sarvaswara moorchanakaraka raga. Raga Mohana and all the resulting ragas (Madhyamavati, Hindola, Suddha Saveri and Suddha Dhanyasi ) are examples of sarvaswara moorchanakaraka ragas.

Srutibheda can be applied to both janaka and janya ragas. Only janaka ragas can be obtained from janaka ragas. Likewise, oudva ragas can be obtained from oudva ragas and shadava ragas from the shadava ragas. Ragas having oudava-shadav, shadava-sampoorna, oudava-sampoorna, etc. result in ragas having exactly similar scale patterns. In such ragas only a note that appears as a common note in their arohana and avarohana can be made as tonic notes or moorchana swaras. Swaras which have transient characters (known as alpa swaras ) cannot be used as moorchana swaras.

For srutibheda to be successful, the given raga and the moorchana swara should meet the following conditions :

1. In the resulting raga there should not be two madhyama swaras appearing one next to another. A prati madhyama which comes next to suddha madhyama is called a chyuta panchama. A scale having chyuta panchama is considered invalid.

2. No gandhara swarasthana should come next to two rishaba swarasthanas and no rishabha swarasthana should come immediately before two gandhara swarasthanas.

3. No nishada swarasthana should come next to two dhaivata swarasthanas and no dhaivata swarasthana should come immediately before two nishada swarasthanas.

Only when these conditions are satisfied, can a new raga result from srutibheda process. It is not necessary that the resulting raga have a name. In fact, many of the shadava, oudava and swarantara ragas do not have names.

In the context of srutibheda, the term raga is referred in the usage of pure notes defined in its scale. It excludes the use of gamakas since the transformation of gamakas under modal shift of tonic is quite complex and leads to invalid gamakas in the transformed raga.

2.3 Srutibheda chakras

It may be observed from the above that the set of ragas originating from a given raga through the srutibheda process, taken together with the starting raga, forms a closed set that is essentially cyclical in nature. This means that the ragas belonging to this set may be derived from one another through the choice of appropriate moorchana swaras. This cyclic set is called here as a srutibheda chakra. In Sanskrit chakra means ‘cycle’ and hence the name. In other words, all the ragas that may be related to one another through the process of modal shift of tonic form a sritibheda chakra. Note that no other raga from outside this set can come into it. Thus the srutibheda chakras are closed sets.

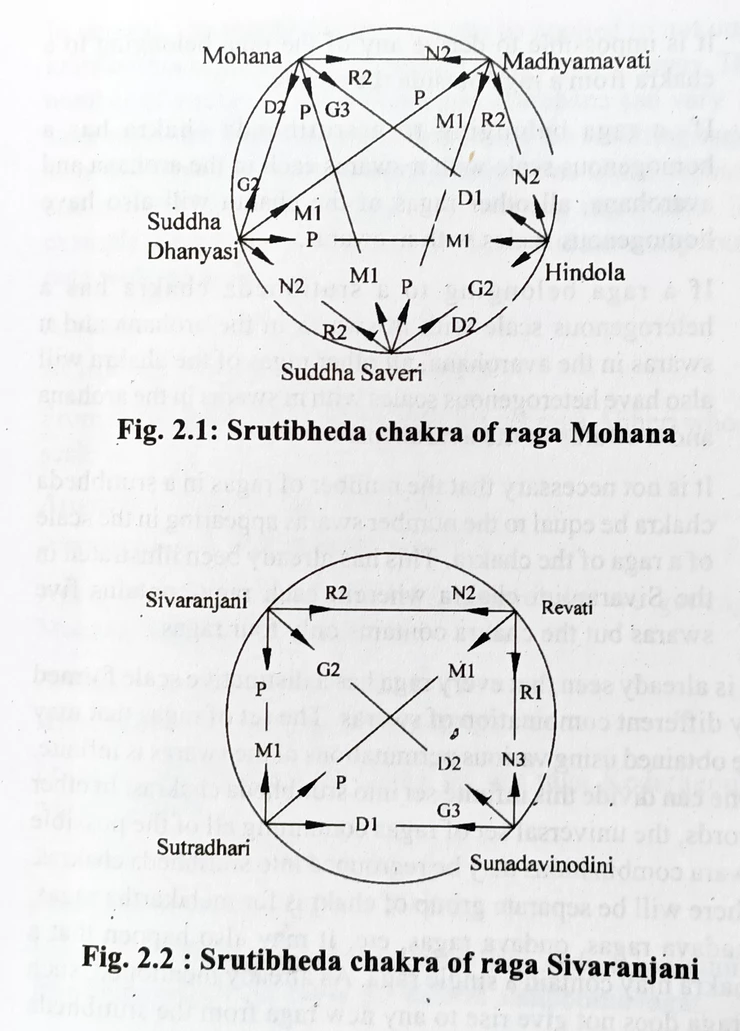

As an example, the srutibheda chakra formed by the raga Mohana and its derivatives, namely, Madhyamavati, Hindola, Suddha Saveri and Suddha Dhanyasi, is shown in Fig.2.1 As can be seen, every raga in the chakra can be derived from every other raga of the chakra employing the moorchana swaras as shown by the arrows.

Every note of Mohana raga, produces a new raga by the srutibheda process and so do the other ragas of this chakra. In general, however, it is not necessary that every note of a raga give rise to a new raga. For example, an oudava raga may give rise to only three new ragas. But even such ragas form srutibheda chakras and are governed by the laws applicable to these chakras. These laws are described later in this chapter. Consider, for example, raga Sivaranjani and its srutibheda derivatives. All these ragas are kramaswara ragas and it is sufficient to describe their scale using only the arohana patterns (The avarohana has the same swaras as in the arohana but appear in the descending order in these ragas.) The swaras appearing in the arohana of raga Sivaranjini are as follows:

S R2 G2 P D2 Ṡ

This raga generates the following ragas:

1. Raga Revati from rishaba (R2) described by the scale

S R1 M1 P N2 Ṡ

2. Raga Sunadavinodini from gandhara (G2) described by the scale: S G3 M2 D2 N3 Ṡ

3. Raga Sutradhari from panchama described by the scale :

S R2 M1 P D1 Ṡ

Note that no raga results when dhaivata (D2) is made as the moorchana swara.

The srutibheda chakra of these ragas is illustrated in Fig. 2.2. It is seen that this chakra contains only four ragas although each constituent raga has five swaras. This is because no ragas originate from the dhaivata of Sivaranjani, panchama of Revati, madhyama of Sunadavinodini and rishabha of Sutradhari.

…..to be continued