Chapter 2

The Sanketi origin

Ranjani Govind

Photos by Rudrapatnam S. Ramakanth

R.K. Srikantan belongs to a community called Sanketi in Karnataka. Known for the community’s role in serving the cause of music and fine arts for hundreds of years, Sanketis in the State are synonymous with sangeetha. Not that their achievements were anything less otherwise! Known for their penchant for hard-earned money, something that also reflected their middle class status and economic conditions, their life is an explanation of a focused journey in their respective vocations. These traits resonate in the villagers’ vocal description of them. “Striving hard to be matchless in anything, they dealt with a Sanketi-trait that has enabled the community become a model for sincerity and hard work.”

There is no official study and information that explains the faithful history behind this devout Veda-practicing community (sect following Advaita, propagated by Adi Shankaracharya; and most Sanketis follow the Sringeri Sharada Peeta) who continue to take forward their deep-rooted genealogy in music.

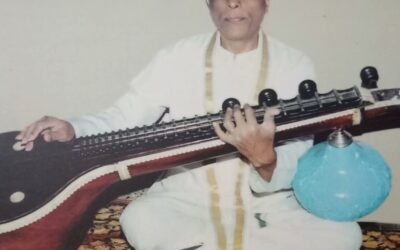

It is in fact difficult to find writers or historians who are able to trace with certainty the exact origins, facts and actualities behind the community’s en masse migration to settle down in the Sanketi villages in Karnataka. In music and literature, Sanketis have excelled as Carnatic vocalists, instrumentalists, composers, lakshana granthakaras, gamaka singers and teachers, while Sanskrit & Vedic scholars and pundits too were in abundance.

The community, never known for being affluent and wealthy, is yet famed for its striking intelligence and hard work. Sanketis are even famed for their knowledge in growing areca palm and hoge soppu (tobacco leaves) and are also adept in making cups from natural banana fibre, known as donne in Kannada.

So who are these Sanketis? Where did they originate from? And what makes up their language?

Sanketis are considered to be an off-shoot of the Iyer community. It is a general belief amongst the Sanketis that it was roughly 900 years back that they set foot here and are now mainly living in Karnataka. Originally from the area of Shencottai (Tirunelveli district) in the border area of Kerala and Tamil Nadu, they initially came to Kaushika near Hassan and Bettadapura in Mysore district and then spread to other villages in the State.

The four predominant groups amongst them are – * Kaushika Sanketi; * Bettadapura Sanketi; * Mattur-Hosahalli Sanketi; and * Lingadahalli Sanketi.

Srikantan belongs to the Bettadapura clan.

Kendra working for the interest of Sanketis…

There are more versions available from the Samudaya Adhyayana Kendra (Study Centre) in Mysore steered by B.S. Pranatartiharan, formerly with Akashavani (AIR). The Kendra works for the interest of Sanketis, it researches, publishes and documents material available on Sanketis, runs a journal, and has activities to safeguard its culture and language. It has also brought out a 20-volume series – Sanketi Studies – containing a compilation of various articles on Sanketis that offers features and descriptive facets on the life of the migrated community.

* One version holds a legend that Sanketis migrated from Shencottai in Tirunelveli District of Tamil Nadu to Karnataka about 900 years ago during the Pandya rule. Interestingly, the story associated with this move sounds like a fairy tale. A pious Brahmin lady, Nacharamma, seeking a way out of the family’s poverty, comes under the spell of a yogi. He offers a ‘divine herbal concoction’ to this family of husband, wife and child – not before warning them that the brew once gulped would bring forth some disastrous, frightful and conquering consequences! He prophesies that the effect would at once be noticeable and apparent on its members. Amongst the three, one would die, another would be struck with a mental disease before demise and the third, the survivor, would be blessed with an abundance of spiritual knowledge. The incident would also lead to having a community of followers for the survivor, setting the beginning for affluence and learning amongst the Sanketis.

It was Nacharamma who survived. The divine intervention heaped upon her a Vedic comprehension so profound and intrinsic that other Brahmins of the town got envious and resentful, especially on occasions when Nacharamma took part in spiritual functions and Vedic debates. The disrespect shown soon after was at a religious gathering when a green-eyed group gifted a sari to Nacharamma with soapstone powder smeared on it. The deception was in asking her to wear the sari before she served food to the people congregated there.

Noticing the sari endlessly slipping away and smelling foul play by the tricksters, Nacharamma instantly devices a smart ‘knot on the left shoulder’ – ghanti or ghandi seere – that fastens itself safely to the body, a style that she created nine centuries ago for the Sanketi clan! But peeved with the never-ending negative vibes around her, Nacharamma decides to abandon her birthplace, leave her soil of origin in search of greener pastures. It is said that two hundred families faithfully followed her. The large assemblage, after crossing various regions in the Kerala and Tamil Nadu borders, reaches Hassan (near Halebidu), which was then under the Hoysala Kingdom.

* Another version has it that the migratory route of the Sanketis took them through Kerala and then Coorg (Mercara) in Karnataka. It is close to the present day Kushalnagar in Coorg. There the local chieftain and his men kidnapped the Sanketi women. The Sanketi men settled outside the chieftain’s settlement and waited for their women to head back. The women ultimately returned to their men folk and settled down at Bettadapura which is around eight kilometers from Kushalnagar. This is one explanation for the Bettadapura Sanketis who initially chose to settle near a hill and not a river. This also spells out an important similarity factor of the Sanketi women and the Coorgi women’s sari-drape which is different from the conventional South Indian sari draping.

* A third theory on Sanketis holds that many families had moved to Devalayam towns in nearby Kerala adjoining Tirunelveli district. For managing the temple and town, the elected body framed rules known as ‘Sanketa’ and the people bound by the rules came to be known as ‘Sanketis.’ The elected head was known as ‘Sabhaiar’ and his wife was addressed as ‘Nacharamma.’ As the community was known to be generally peaceful under the Zamorins of Travancore and Malabar, the social, religious and political reasons for their migration to up-ghat Kannada regions are not known with any certainty.

Several books from the Samudaya Adhyayana Kendra have authors speculating the fact that after the advent of the Portuguese on the West Coast, the quiet life of the people must have been disturbed and they must have scaled the Western Ghats and reached Periyapatna, the capital of the then Kannada Kingdom. Mysore State came into existence only by the end of the 16 th Century when Raja Wadiyar vanquished Srirangaraya, the representative of Vijayanagar Empire which broke up after the Talikota War in 1565.

After the downfall of the Hoysalas, the Sanketis spread out to places on the banks of the Cauvery, Hemavathi, Lakshmanatirtha and Tunga. One group went to Kaushika in Hassan district, another to Bettadapura in Mysore district and some more to Lingadahalli, Mattur and Hosahalli near Shimoga and another section to Malenadu and Hiriyangala in Kadur taluk of Chikmagalur district. Gradually they came under the local rulers and chieftains and worked in lands surrounding the rivers with agriculture being their mainstay.

Sanketis who came in search of work spread to nearly 50 villages in the precincts of Hassan and Mysore in villages such as Rudrapatna, Basavapatna, Keralapura, Bettadapura, Saligrama, Ramanathapura, Konanooru, Kattepura, Kanagaalu, Saragooru, Kushaalanagara, Kaniwe, Periyapatna, Chilakunda, Harave, Hunasooru, Hanasoge, Edatore (K.R. Pet), Tippooru, Gaavadagere, Kuppalli, Halli-Mysooru, Mosale, Somanahalli, Agrahaara, Magge, Baragooru, Maavinakere, Maritammanahalli, Shantigrama, Pomagaame and Hundraalu.

The name ‘Sanketi’ is said to have evolved over generations as their ancestors were believed to be from Shencottai, or so-coined because the migrants came without a ‘Sanketa’, are explanations given in some of the books on Sanketi literature.

Language of the Sanketis…….

Analysts say the culture and lingo of several geographical regions that the community traversed along, bordering the southern states, must have left strong imprints on this large faction, as the Sanketi dialect gathers a curious mix of Kannada, Tamil and Malayalam, along with a smatter of words sprinkled here and there in Kodagu, Tulu, Telugu and Sanskrit. It is also said that several families who chose to remain in the Kerala-Tamil Nadu border villages still retain their original Sanketi tongue that is left un-influenced in its language, as against the migrants’ adaptation of several other vernacular expressions.

The Sanketi language is distinct from Kannada and Tamil and is known for its independent standing, according to Dravidian linguists such as Hampa Nagarajaiah. Many still call it a dialect of Kannada in keeping with tradition, but many in the Sanketi families say that for a person conversant with Kannada, Tamil or Malayalam it would be easier to follow the flow.

Linguists say Sanketi, to a large extent, has been influenced by and borrowed from Kannada and Sanskrit; at the same time much of its language retains its original character. It shares similarities with Malayalam as well, as it is believed to have originated from Shencottai where the clan is traced from. Sanketi has also retained the proto-Dravidian elements in various expressions.

The language has a rich vocabulary. Some Sanketi language experts say, as the community is close-knit, a vast terminology of kinship terms has gradually taken shape since centuries. The flow is highly developed now, and perhaps the Hebbar Iyengars, Mandyam Iyengars or people from the Hassan-Mysore belt of Karnataka would be the closest to understanding the Sanketi language better, as these sects are familiar with a mix of Kannada and Tamil terminologies that they themselves use.

Consider this:

Bettadapura Sanketi lingo:

Odappa Nandaarandya, Hatulle ellaru apti ranne? (Are you well? How is everyone doing at home?)

Nangella nandaarano, ningella apti randigo? (We are all fine, how are all of you?)

Koushika Sanketi sampling:

Vod, shaane tadechitta maayittu paper vodandran dye Avadhani? (Hey! you are really immersed in reading the paper, Avadhani?)

Indonaththe Paperre sikkitilla. Ado Oruvarshaththe pale Prajavani hathlindi (I didn’t get today’s paper. Some one-year-old Prajavani was lying at home.) Adtha Aldirandh? (What is it that is written?) Odaani Kolu (I will read, you listen)

Explains a senior Sanketi Narayanappa at a village bordering Mattur, “There is much emphasis laid on singular and plural references (as in casual or respectful mentions) as used in other developed languages – Avha (reverential reference); Avu(n) (with due respect); and Adu (he, she). Pashsha in Koushika Sanketi means children, also referred as Paije in Bettadapura lingo. Pashsha Varandu (children are coming).

There is also a clear demarcation in the tenses and in the first, second and third person usages. There are three genders in the language in Sanketi references, and a clear segregation exists between the inclusive and non-inclusive pronoun – nAnga -engaDE versus the nAmba/nAma, nammaDE/nambaDE. One feature which is unique to the Sanketi language is the much in use neuter gender, for referring to a child or someone closely related.

Having come to Karnataka via Kerala, this community is said to have been influenced to take up agriculture by raising areca nut, coconut and betel leaf plantations. Vedadhyayana (the study and practice of spiritual Vedic life) the study of Sanskrit, classical music, theatre and gamaka were lineage traditions that came to them automatically. It is said that it is rare to find Brahmins transform themselves as agricultural workers in fields, but this was one signature aspect of the Sanketis.

Old-timers feel what made Sanketis be fiercely different from the Havyaks of Uttara Karnataka, or the Heggades and the Hegdes of Dakshina Kannada who are amongst the generations of fine agriculturists, was their love for classical music. Melody was part of their work in paddy fields! The evening would not only have these ‘agriculturists’ perform ‘sandhyavandana’ but also have them recite slokas on their way back home. While the female folk sang during their domestic chores, musicians did not hesitate to season their voice standing upright in water!

Sanketis say that the grit and determination of Nacharamma, her resolute mind to sideline the spiteful characters around her and her enterprising approach that helped her lead an entire neighbourhood to embrace another ‘countryside’, are dynamic features that serve as Sanketi mantras for developing an enterprising outlook.

Nacharamma, incidentally, is one of the names of Goddess Lakshmi referred in the Hindu religious texts, and she is bestowed with knowledge (Saraswathi), believe many Sanketi women. If music, agriculture, culinary skills and the Vedas were their vocations, past-time play too was a cerebral one, as Sanketis were adept at card games like 28 (similar to Bridge) and Pagade (a form of dice) while not forgetting to chew on their favourite viledele (betel leaf).

– to be continued

*******